Rebecca Solnit makes getting lost something to aspire to. In her collection of autobiographical essays proving there is no subject out of her reach, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, she maps out various ways to be lost. Lost in place, time, music, conversation, identity, family, society, and so on. She frames getting lost as invitation to discover new things, not least about yourself.

She explains her terms early on:

Lost really has two disparate meanings. Losing things is about the familiar falling away, getting lost is about the unfamiliar appearing. There are objects and people that disappear from your sight or knowledge or possession; you lose a bracelet, a friend, the key. You still know where you are. Everything is familiar except that there is one item less, one missing element. Or you get lost, in which case the world has become larger than your knowledge of it. Either way, there is a loss of control. Imagine yourself streaming through time shedding gloves, umbrellas, wrenches, books, friends, homes, names. This is what the view looks like if you take a rear-facing seat on the train. Looking forward you constantly acquire moments of arrival, moments of realization, moments of discovery. The wind blows your hair back and you are greeted by what you have never seen before. The material falls away in an onrushing experience. It peels off like skin from a molting snake. Of course to forget the past is to lose the sense of loss that is also memory of an absent richness and a set of clues to navigate the present by; the art is not one of forgetting but letting go. And when everything else is gone, you can be rich in loss.

p.22-23

Solnit’s imagery of the rear-facing view on the train immediately grabbed me. (Given current COVID times, I also could not help but add “masks” to the list of quotidian things I would see stream past my window).

But her description also horrified me. She moved from household objects to people in the same breath. You don’t lose a friend in the same way you lose a key or a bracelet. And what about the loss of sons, daughters, mothers, fathers, spouses? Perhaps reading this book in a pandemic has heightened my sensitivity to these human losses that are far from romantic. Would people who have said goodbye to a loved one, or multiple loved ones, describe themselves as “rich in loss?”

Given her topic and her mention of “keys”, I thought Solnit would reference Elizabeth Bishop’s famous poem “One Art” that also talks about loss. In fact, I frequently title this poem “The Art of Losing” in my head since this line is repeated so often in the villanelle. (I’ve actually written on this poem before in Part 1 and Part 2). Bishop similarly moves from talking about insignificant objects like keys to weightier losses like places and houses until she reaches the subject of her poem, the loss of a loved one. It’s like she’s working herself up to be able to talk about the latter, as if by practicing losing keys or “the hour badly spent” will prepare you for losing someone you love. And though she keeps repeating that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master” it becomes apparent through the poem that losing IS hard to master. The villanelle form requires Bishop to repeat that line but the reader gets the sense the speaker is only trying to convince herself. In the last stanza, she falters and concedes that “the art of losing isn’t too hard to master” (emphasis mine). In other words, yes, it is hard.

Whereas Solnit’s description of loss is rather flippant and viewed through rose-coloured glasses, Bishop’s poem doesn’t sentimentalize loss. Considering how erudite Solnit is and how eclectic her references, I thought it a real miss that she didn’t mention Bishop.

I came across this reading of “One Art” by Canadian high school student Sophia Wilcott and had to share it here. She captures the struggle of the poem so well.

That critique aside, there were countless passages in A Field Guide to Getting Lost that I flagged for copying into my journal. Take this section, for example:

Sometimes an old photograph, an old friend, an old letter will remind you that you are not who you once were, for the person who dwelt among them, valued this, chose that, wrote thus, no longer exists. Without noticing it you have traversed a great distance; the strange has become familiar and the familiar if not strange at least awkward or uncomfortable, an outgrown garment. And some people travel far more than others. There are those who receive as birthright an adequate or at least unquestioned sense of self and those who set out to reinvent themselves, for survival or for satisfaction, and travel far. Some people inherit values and practise as a house they inhabit; some of us have to burn down that house, find our own ground, build from scratch, even as a psychological metamorphosis.

p.80

Even though she puts people into two generic categories, is it not fairly accurate? (It reminded me of my niece when she was young who would go around saying: “There are two kinds of people in the world” followed by whatever she observed that day: “those who close the door and those who open the door” or “those who talk and those who don’t” and she would come up with all sorts of contrasts that were actually very illuminating). Even though it’s obvious that Solnit puts herself in the travel-far-from-home-to-find-yourself camp, I feel she is kind and even a bit in awe of those who grow up with an “unquestioned sense of self.” There is something to admire about both paths as long as they don’t lead to self-righteousness and closed-mindedness.

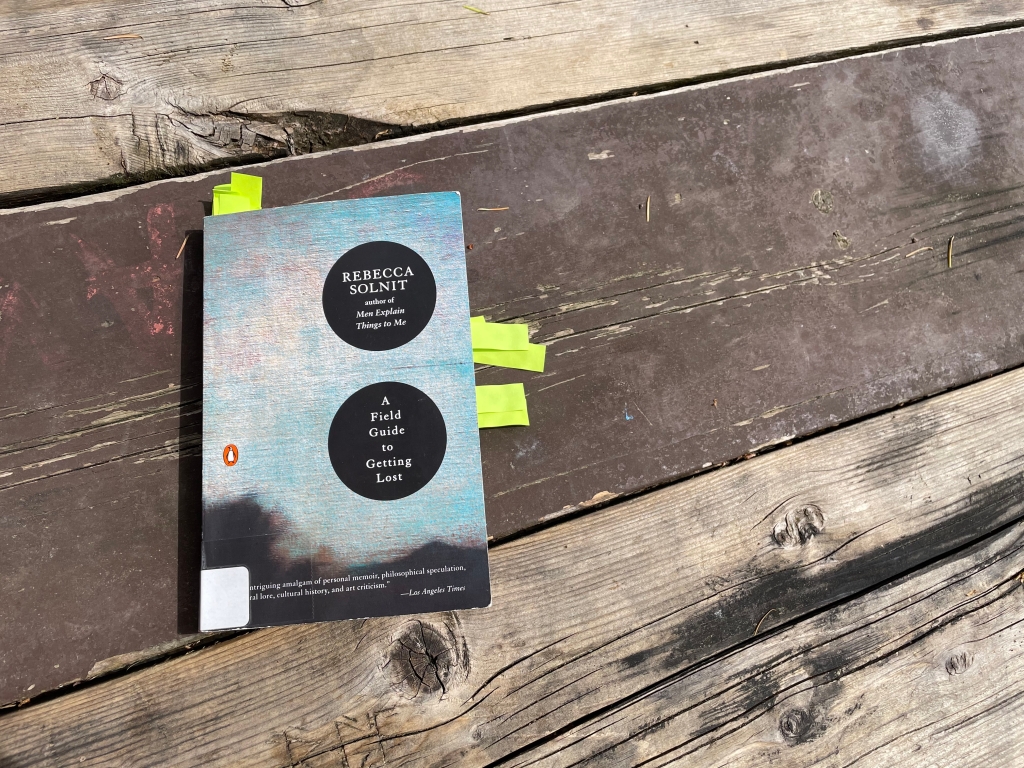

Those are just a few thoughts I wanted to pull out from this meandering but delightful book. (When you’ve flagged so many passages in a library book, it feels necessary to just buy it). Here’s an actual review of the book by Josh Lacey in The Guardian for those of you whose appetite may be whet and want to know a bit more about it.